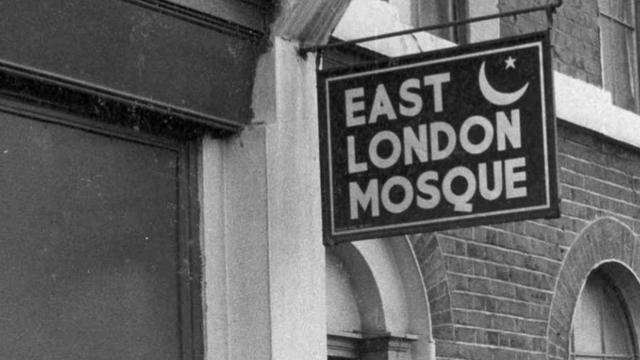

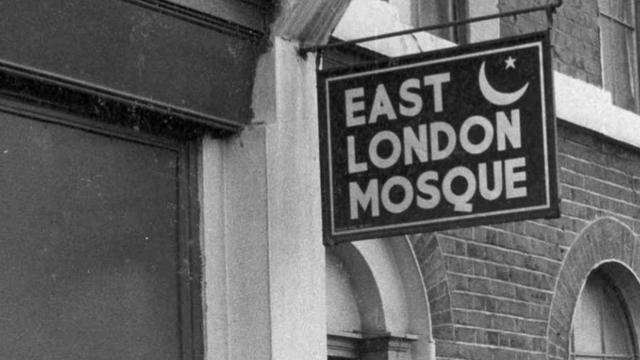

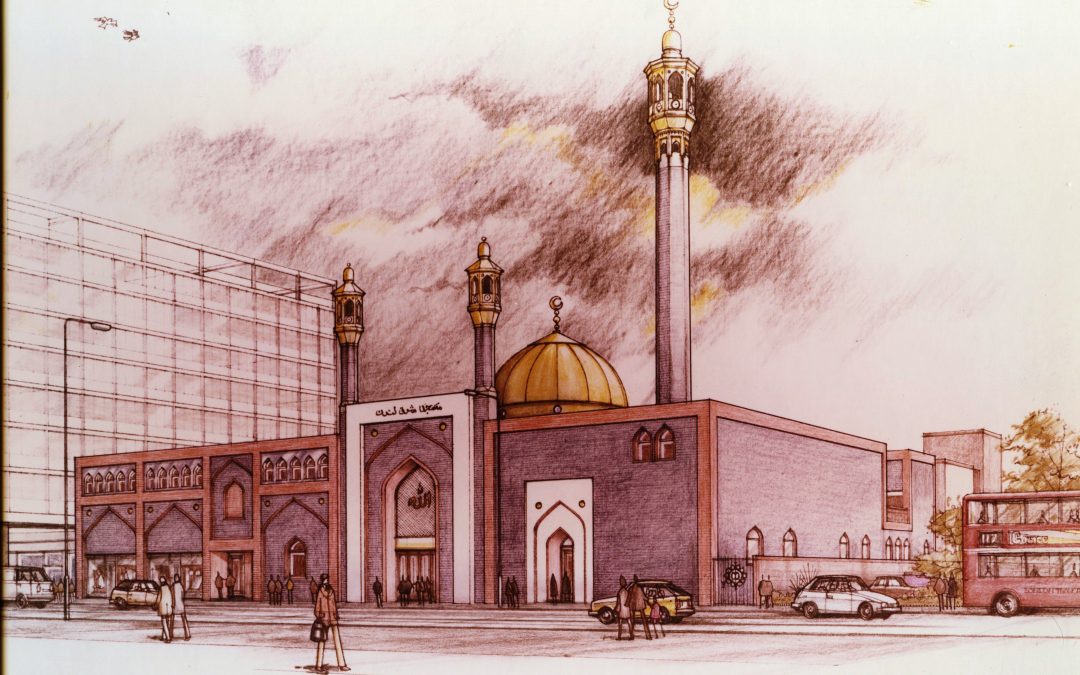

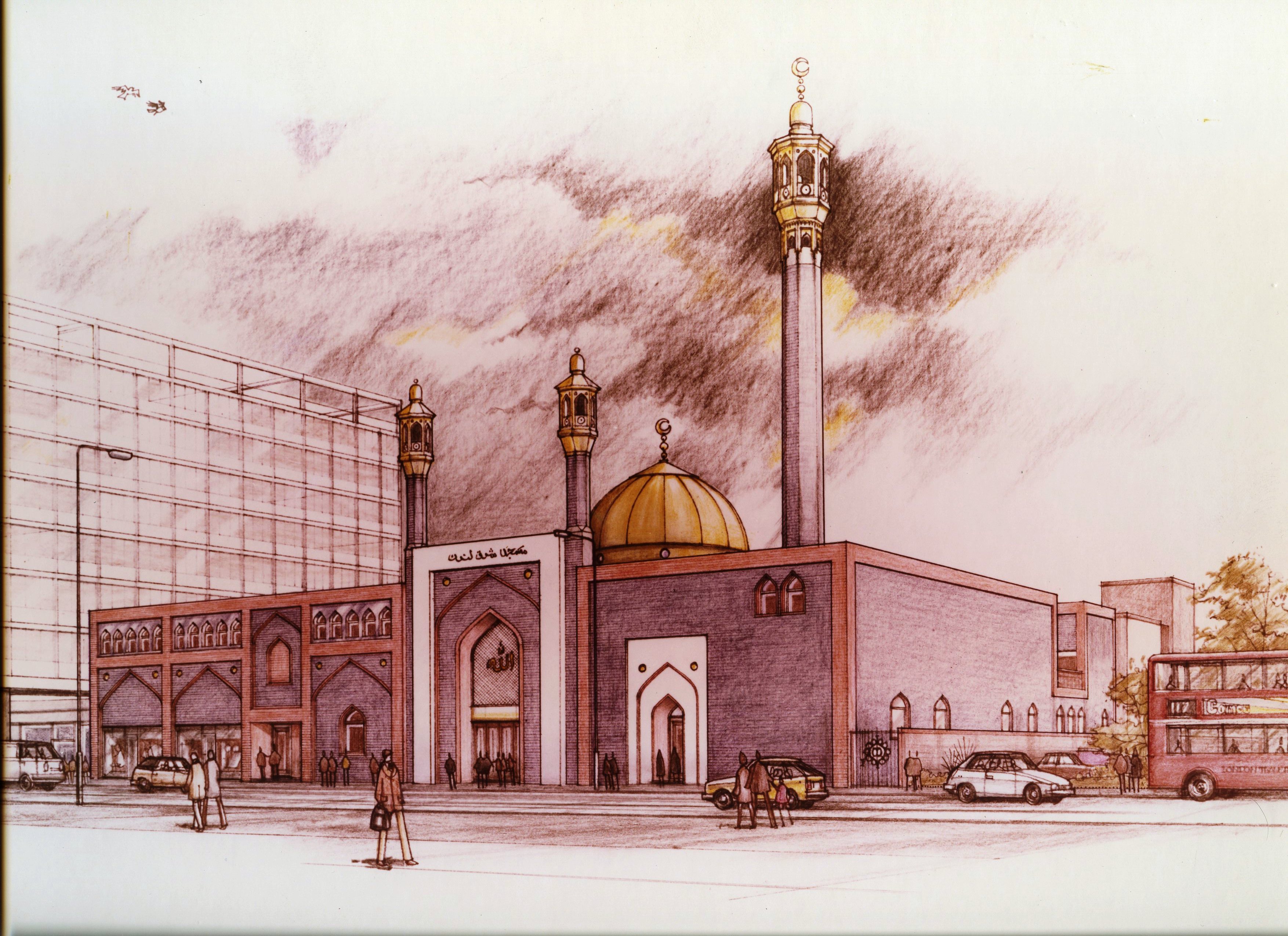

On the South side of Whitechapel Road in East London between Aldgate East and Whitechapel Tube stations sits the gold dome of the East London Mosque. For some, it is one of many exotic shapes cropping up all over Britain; for local Muslims it is perhaps more synonymous with the area than the Tower of London; and for others still, it is a slice of East End Nouveau. But what is less known is that the East London Mosque as it currently stands is the descendent of a previous mosque that was established seventy years ago over three decades from 1910 — a mosque that owed its existence to the highly collaborative vision and efforts of a diverse group of early educated Muslims and non-Muslims.

It is my intention in the following pages to offer a précis account of this history, of how the first Mosque in London came to be through a selective exploration of an eclectic roster of the personalities involved. Our journey begins with the original vision of erecting a Mosque in London at the end of 1910 and the establishment of the London Mosque Fund; through the difficulties brought about by colonial wars, World War One, the Great Depression; leading into World War Two, during which the first permanent mosque premises was established in 1941 on Commercial Road in East London: the East London Mosque and Islamic Cultural Centre.1

At the beginning of the 20th Century the dream of a mosque in the capital of the British Empire was shared by a handful of English-educated Muslims and a number of sympathetic non-Muslims connected to the Muslim world through colonial channels. Two separate projects were shared amongst the members of this group, with the common goal of building a mosque in London. These projects

were the London Nizamia Trust and the London Mosque Fund. Even though both projects shared some of the same trustees, the logical step of a merger was never taken in order to complete the project and fulfil a seemingly symbiotic dream. The most probable reason cited has been ‘religious differences’2; however, these differences did not prevent the group working together for

In 1905 the first ‘Eid Prayer… was arranged

in London by the Rt. Hon. Syed Ameer Ali and Abdullah Suhrawardy.

a number of years towards the exact same goal through the two projects; a goal that would first be achieved from the treasury of the London Mosque Fund in 1941.

In 1905 the first ‘Eid Prayer (Muslim prayers accompanying one of two festivities in the lunar calendar) was arranged in London by the Rt. Hon. Syed Ameer Ali and Abdullah Suhrawardy. Despite appalling weather conditions, the prayer was held outdoors in Hyde Park with a number of prominent British Muslims in attendance. This event continued the highly convivial ‘Eid gatherings that had taken place thirty miles south of the capital at Woking Mosque in previous years and would have most certainly inspired much of the energy needed to establish a mosque in London over the following decades.

Five years later a public meeting was arranged by the Rt. Hon. Syed Ameer Ali at the newly built Ritz Hotel on the 9th of November, 1910. Under the Chairmanship of the Rt. Hon. Sir Sultan Mohammad Shah Aga Khan (spiritual leader of the

Biography of a Mosque: The story of London’s first Mosque, 1910-1942

Ismaili Muslim community) the meeting resolved to raise funds for the purpose of establishing “a Mosque in London worthy of the traditions of Islam and worthy of the capital of the British Empire”.3 To this end, and to manage the ‘London Mosque Fund’ (LMF), an Executive Committee would form under the Chairmanship of the Rt. Hon. Syed Ameer Ali, a man of considerable energy and vision.

AretiredHighCourtJudgeandhighly connected Shi’a Muslim from Calcutta,4 Ameer Ali was the first Muslim to be appointed to the Privy Council in 1909 and was a strong advocate on behalf of the Muslim community in Britain and around the world. Apart from his widely acclaimed scholarly works, A Short History of Saracens (1898) and The Spirit of Islam (1891), he regularly penned letters and articles to British newspapers commenting on local and global current affairs. He was one of the founding members of The All- India Muslim League who also wrote and lectured on the position of women in Islam, perhaps un-coincidentally during the height of the suffragette movement in Britain. Working tirelessly on his various activities until his death in 1928, Ameer Ali’s pan-Islamic and humanitarian concerns led him to found the British Red Crescent Society in 1919 which he used as a platform for action. In 1924 he wrote a letter to the Times appealing for public donations on behalf of the Red Crescent Society to ease the suffering of women, children, wounded and prisoners who were victims of Spain’s bombardment of Morocco in 1924.5

A few months after that initial meeting of the LMF in 1910 The Times published a brief report by the Rt. Hon. Syed Ameer Ali including the names of the Fund’s trustees and the intention to raise money for a mosque in London including an Islamic library and reading room, and arrangements for lectures to be delivered after the weekly Friday sermon.6

In the first two and a half decades of the London Mosque Fund the trustees were kept busy by seeking local and international support through donations and patronage.

As interest in the project spread, along with requests for donations from global Muslim leaders and aristocracy, donations began to make their way into the LMF coffer. Included was patronage and contributions of £1000 each from The Sultan-Caliph Muhammad V and the ex-Shah of Persia; The Nizam of Hyderabad (25,000 rupees), and £1000 from H.E.H Asaf Jah Nizam- ul-Mulk (the Nizam’s successor); as well as subscriptions from Persia. Muslim rulers offering their patronage to the LMF included Habibullah Khan; Amir of Afghanistan and Sultan Sayyid Khalifa bin Harub Al-Busaid, the Sultan of Zanzibar, and a number of Malay Sultans.7 The Begum of the Indian state of Bhopal offered the London Mosque Fund a donation of seven thousand pounds8 on the condition that a student hostel would be annexed to the Mosque and that Muslim students’ dietary provisions would be catered for. This followed in the footsteps of her Mother, the previous Begum, a generous supporter and namesake of the Shah Jahan Mosque in Woking. The Begum’s £7,000 never materialised. Patrons and Absentee members of the Executive Committee also included His Highness the Sheikh- ul-Islam (the highest scholarly authority in Islam) and Their Holinesses the Chief Mujtahid of Najaf and the Chief Mujtahid of Tehran (equivalent of Sheikh-ul-Islam in the Shi’a tradition)9. H.M. King George V was also surreptitiously approached to patronise the project,10 but the then Secretary of State for India, Lord Morley advised him against it resulting in a refusal by the King’s office.11

Despite the attention the London Mosque Fund garnered from Muslim rulers, the LMF amounted to only 6,131 pounds, 13 shillings and 10 pence, a figure well short of what was needed to begin mobilising a team of architects, particularly while still in need of a suitable location. An article by the Fund’s Chairman was published in the Westminster Gazette in 1917 describing the aims of the LMF and its current function of “maintaining a Moslem place of worship at 111 Campden Hill Road, Notting Hill (London), to meet the spiritual needs

of the growing Moslem community in London”.12 At this time, Friday (Jumu’a) prayers in London were sponsored by the LMF which allocated £120 per annum up until 1928. Jumu’a had previously been conducted at Lindsay Hall, Notting Hill Gate West, and 39 Upper Bedford Place. The Westminster Gazette article also accurately predicted the influx of Muslim visitors and migrants to Britain once the war was over.

While symbolic support for the fund was plentiful and encouraging, with a number of high-profile dignitaries included on its list of patrons, the LMF’s Chairman, Syed Ameer Ali later expressed his disappointment that more money had not been raised to get the project beyond the hall-hiring stage as he laments:

I perceive with sorrow that there appears to be, for some occult reason, a general decline of interest in the furtherance of duties enjoyed by their religion among the rich Muslims of India. With some notable exceptions, magnates and ruling chiefs, whilst ready to contribute lavishly to objects favoured by Government functionaries, tighten their purses when an appeal is made to them for a pious or a religious purpose with every guarantee for its proper performance13.

Along with international Muslim interest and an influx of financial contributions into the LMF, it also held in its practical service a diverse array of prominent British personalities: colonial civil servants, Lords, academics, writers, politicians, educators, along with a number of officers in the diplomatic service from all over the Muslim world. Around the table of the first official meeting of the LMF Executive Committee on December 13th, 1910 in Caxton Hall sat prominent British educationist, diplomat and writer Sir Theodore Morison, author of a number of works on India’s economy and renowned educationist.14 Sitting perhaps to his right was Khalil Khalid Bey, an Ottoman diplomat and eventual teacher of the Turkish language at Cambridge University. Bey was a prolific writer in the early part of the 20th century, best known for his autobiographical work

The Diary of a Turk (London, 1903) and The Cross versus the Crescent (London, 1907). He is also considered one of the first writers against ‘Orientalism’.15 Maybe sitting across from him was Alibhai Mulla Jeevanjee, an Indian entrepreneur and newspaperman operating mostly out of Nairobi. Jeevanjee founded the Jeevanjee Market in downtown Nairobi and the first English language paper in Kenya, the African Standard.16 Also in attendance was a London-based precious stone merchant and Vice President of the All India Muslim League (AIML),17 Camrudin Amirudin Latif, who would serve the LMF as Honorary Secretary from March 1911 until his resignation in December of 1925.18 Latif would then be replaced by Professor Thomas W. Arnold, a renowned orientalist academic and long-time friend of Sir Theodore Morison. Professor Arnold’s The Preaching of Islam (1913) was a meticulously researched publication dealing with the prevalent myth that the propagation of Islam occurred wholly by the sword.19

Both Morison and Arnold had taught at Aligarh Muslim University (formerly Muhammedan Anglo-Oriental College) in the late nineteenth century: Arnold, Islamic Studies, and Morison, English.20 Arnold would commit his support to the LMF for twenty years until his passing on the 9th of June, 1930. Also included among the early trustees of the LMF was Lord Nathan Mayer Rothschild, First Baron, of the well-known Jewish banking family. While there is no record of Lord Rothschild ever attending a meeting, he was named as a trustee in a Times article in 1911(see Endnote 4). After his passing in 1915,21 Lord Rothschild was succeeded by the Rt. Hon. Lord Lamington (2nd Baron), who had served the Crown as governor of Queensland (1896-1901) and Bombay (1903-1907).22 He joined the Rt. Hon. Lord Ampthill (2nd Baron), who had joined the LMF immediately after its inception and had served the Crown as the Governor of Madras23 from 1900 to1905. Ampthill also briefly held the office of Interim Viceroy of India in 1904.24

of the growing Moslem community in London”.12 At this time, Friday (Jumu’a) prayers in London were sponsored by the LMF which allocated £120 per annum up until 1928. Jumu’a had previously been conducted at Lindsay Hall, Notting Hill Gate West, and 39 Upper Bedford Place. The Westminster Gazette article also accurately predicted the influx of Muslim visitors and migrants to Britain once the war was over.

While symbolic support for the fund was plentiful and encouraging, with a number of high-profile dignitaries included on its list of patrons, the LMF’s Chairman, Syed Ameer Ali later expressed his disappointment that more money had not been raised to get the project beyond the hall-hiring stage as he laments:

I perceive with sorrow that there appears to be, for some occult reason, a general decline of interest in the furtherance of duties enjoyed by their religion among the rich Muslims of India. With some notable exceptions, magnates and ruling chiefs, whilst ready to contribute lavishly to objects favoured by Government functionaries, tighten their purses when an appeal is made to them for a pious or a religious purpose with every guarantee for its proper performance13.

Along with international Muslim interest and an influx of financial contributions into the LMF, it also held in its practical service a diverse array of prominent British personalities: colonial civil servants, Lords, academics, writers, politicians, educators, along with a number of officers in the diplomatic service from all over the Muslim world. Around the table of the first official meeting of the LMF Executive Committee on December 13th, 1910 in Caxton Hall sat prominent British educationist, diplomat and writer Sir Theodore Morison, author of a number of works on India’s economy and renowned educationist.14 Sitting perhaps to his right was Khalil Khalid Bey, an Ottoman diplomat and eventual teacher of the Turkish language at Cambridge University. Bey was a prolific writer in the early part of the 20th century, best known for his autobiographical work

The Diary of a Turk (London, 1903) and The Cross versus the Crescent (London, 1907). He is also considered one of the first writers against ‘Orientalism’.15 Maybe sitting across from him was Alibhai Mulla Jeevanjee, an Indian entrepreneur and newspaperman operating mostly out of Nairobi. Jeevanjee founded the Jeevanjee Market in downtown Nairobi and the first English language paper in Kenya, the African Standard.16 Also in attendance was a London-based precious stone merchant and Vice President of the All India Muslim League (AIML),17 Camrudin Amirudin Latif, who would serve the LMF as Honorary Secretary from March 1911 until his resignation in December of 1925.18 Latif would then be replaced by Professor Thomas W. Arnold, a renowned orientalist academic and long-time friend of Sir Theodore Morison. Professor Arnold’s The Preaching of Islam (1913) was a meticulously researched publication dealing with the prevalent myth that the propagation of Islam occurred wholly by the sword.19

Both Morison and Arnold had taught at Aligarh Muslim University (formerly Muhammedan Anglo-Oriental College) in the late nineteenth century: Arnold, Islamic Studies, and Morison, English.20 Arnold would commit his support to the LMF for twenty years until his passing on the 9th of June, 1930. Also included among the early trustees of the LMF was Lord Nathan Mayer Rothschild, First Baron, of the well-known Jewish banking family. While there is no record of Lord Rothschild ever attending a meeting, he was named as a trustee in a Times article in 1911(see Endnote 4). After his passing in 1915,21 Lord Rothschild was succeeded by the Rt. Hon. Lord Lamington (2nd Baron), who had served the Crown as governor of Queensland (1896-1901) and Bombay (1903-1907).22 He joined the Rt. Hon. Lord Ampthill (2nd Baron), who had joined the LMF immediately after its inception and had served the Crown as the Governor of Madras23 from 1900 to1905. Ampthill also briefly held the office of Interim Viceroy of India in 1904.24

During the early years of the LMF, the issue of a fitting location for London’s first mosque was the subject of fervent discussion. It was resolved that “the matter be looked into [more] thoroughly as the Mosque was being built for all times and it must be commensurate with the dignity of Islam”. British solicitor and Unionist politician, Sir William Bull was insistent that “the site be in the centre of the Empire”,25 and with some sympathy from the County Council, on the river, in Westminster.

Before the suggestion of where to build a mosque could be fruitfully investigated, Europe would find itself at war. And so with the advent of the ‘Great War’, the ingredients were gathered that would begin to ferment into Ameer Ali’s prediction only a few years earlier. Immediately after Britain’s declaration of war with Germany, 8000 British merchant seamen had joined the army and 9000 ‘enemy’ seamen had lost their jobs causing a mass shortfall of labour in the British shipping industry. This prompted a surge of Muslim immigrants from the British colonies to arrive in shipping yards all over the country to fill the gaps in the wartime labour market in service of the Empire.26 These were not the only Muslim subjects to serve the Empire. A considerable number of Muslim soldiers (Lascars27) also fought, with 400,000 Muslims enlisted by Armistice Day, 60,000 deceased, 13,000 medals with 12 Victoria Crosses awarded.28 The Lascars would also make a tremendous contribution to the Second World War effort with approximately half a million, mostly Punjabi Lascars enlisted.29 Many of the ‘lascars’ employed in the shipping industry would chose to settle in Britain, forging the first link in the migration- chain from the Indian sub-Continent. It wasn’t until a few years after WWI that the London Mosque Fund revived its activities and on the 19th of November, 1926 it was declared a Trust for the “… erection and maintenance in London of a fitting Mosque to be used by Moslems in London and Moslems visiting London from any part of the world for worship

Signatories of the Trust Deed[included]

…Shah Aga Khan, Rt. Hon. Justice Syed Ameer Ali; the Rt. Hon. Charles WallaceCochrane-Ballie Baron Lamington; [and] the Rt. Hon. Arthur Villiers Russell Baron Ampthill.

according to the religion of Islam and until such erection to provide for such worship in any manner which may be deemed expedient”.30

Signatories of the Trust Deed would include: H. H. Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan, Rt. Hon. Justice Syed Ameer Ali; the Rt. Hon. Charles Wallace Cochrane-Ballie Baron Lamington; the Rt. Hon. Arthur Villiers Russell Baron Ampthill, and Sir Muhammad Rafique.31 Now an official Trust, the LMF’s Chairman initiated a new funding drive across the Muslim world as well as appealing to the British Government for support, arguing that a state sponsored mosque would serve to commemorate the contribution of Muslims to the war effort in the same way the French government had done by erecting the Moorish, Grande Mosquée de Paris in 1926.32 The Government again responded adversely. Soon after this the LMF lost its main driving force and visionary founder, the Rt. Hon. Syed Ameer Ali who passed away on the 3rd of August, 1928 at the age of 79.33 Lord Lamington then assumed the Chairmanship of the LMF.

The LMF’s fundraising activities had already been delayed by the outbreak of three wars involving Muslim territories: The Tripolitan War (1911), the Balkan War (1912-13), and later the First World War (1914-18), along with the passing of the LMF’s Chairman, Hon. Secretary (T. W. Arnold in 1930) and Sir Muhammad Rafique. With the arrival of the Great Depression, and an increasing number of

Muslim settlers in London in the early 1930s, particularly the East End, the LMF’s Trustees recognised the need for a more geographically focused approach. To accommodate the religious needs of these ‘poor Muslims’ the London Mosque project would adopted a more philanthropic, local character.34

In the late 1930s the trustees eventually agreed to move the Friday and ‘Eid Prayers from West London to appropriate venues on Commercial Road in the East End, first making use of Queen’s Hall and then King’s Hall. Despite the economic downturn, the trustees were optimistic, with money still being sought from a number of local and international benefactors. The most generous of these was Osman Ali Khan, Asaf Jah VII, the Nizam of Hyderabad, then considered the richest man in the world35 and namesake of the competing Nizamia Mosque project. The difficulty of not uniting the two mosque projects was becoming apparent and after a two failed attempts in the early 1930s for charitable endowment from the Nizam, Muhammad Marmaduke Pickthall, then in the Nizam’s service, was urged to put a proposal forward on behalf of the LMF.36

Pickthall was a prominent British convert to Islam who had served the Muslim community that met for Friday prayers at Campden Hill Road as the Imam (religious leader) during the early days of the LMF and was then located in Hyderabad working as a university teacher and helping to prepare officers for Hyderabad’s civil service. Most famous for his translation of the Qur’an into English (still probably the most widely used translation), Pickthall was also a gifted novelist and contributor to numerous Muslim causes nationally and globally. One beloved institution that he (along with the Rt. Hon. Syed Ameer Ali and the H. E. The Aga Khan) was loathe to see disappear was the Ottoman Khalifate (Sovereignty). Pickthall, Ameer Ali and the Aga Khan petitioned the British Government not to dissolve the Caliphate after the fall of the Ottoman Empire in the early 1920s;37 to no avail. Even though Pickthall was a close

confidant of the Nizam, the government of Hyderabad itself was under financial strain and the competing project in West London, where the Nizam’s much stronger commitment lay was gaining momentum. Around 1930 the Nizam had pledged £60,000 to the project bearing his name at the behest of Lord Headley, another prominent British convert to Islam.38 Pickthall’s fundraising attempt for the LMF was duly unsuccessful.39

With the recent passing of two stalwarts of the LMF, the need arose to recruit two new members to the board of trustees. These recruits would represent, quite literally, the next generation of leaders. Ameer Ali’s eldest son, Waris Ameer Ali, also a Judge, and Major General Nawab Malik Sir Mahomed Umar Hayat Khan Tiwana, a wealthy Punjabi landowner with a highly distinguished Indian Army career, who would later go on to serve three of England’s Monarchs [George V (1930); Edward VIII (1936), and George VI (1937)] as Honorary Extra Aide-de- camp,40 joined the LMF in early January, 1931.

Theearly1930salsosawtheestablishment of the Jami’at-ul-Muslimin (JuM), an organisation that would later have a lasting impact on the Muslim landscape in East London and Britain, establishing Mosques and Muslim institutions in a number of major cities including Glasgow and Manchester. The JuM was formed in 1934 under the chairmanship of Allama I. I. Kazi, Barrister at Law, philosopher, educationist, and founding Chairman of Sindh University, India. Its broad objectives were to further the observance of Islam and provide help to poor and needy Muslims throughout the world. Unity of the Muslim communities in Britain was also important to the JuM. In its first Annual Report (1934-35) are details of its efforts to unite the Nizamia Trust and the London Mosque Fund by abandoning the mosque project in West London, combine resources and build a mosque in the East End of London which was “the centre of [the] Muslim population and the resort of seamen from abroad”.41 The JuM were active in organising Friday and Celebratory prayers in East London under the auspices of the LMF which provided funding.

More changes to the LMF’s Board of Trustees were to come in the Mid 1930s following the passing and long service of Lord Ampthill on the 7th of July 1935; the resignation of Sir Mahomed Umar Hayat Khan Tiwana; and the appointment of another distinguished military and colonial serviceman Sir Frederick Hugh Sykes, having recently returned from India where he served as the Governor of Bombay.42/43 Before moving into politics, the Rt. Hon. Sir Frederick Sykes completed a highly distinguished military career, retiring from the Royal Air Force in 1919 with the rank of Air Vice-Marshal.44 But unfortunately for the LMF his “manifold other duties” prevented him from remaining a Trustee beyond September of 1941. The passing of Abdeali S. M. Anik in 1939 would also be a blow, ending the longest service given to the London Mosque Fund to that date. A merchant by trade, A. S. M. Anik volunteered his proficiency in financial matters for over twenty-seven years, the majority of which was spent as the Fund’s Honorary Treasurer. His services in this capacity were also given to the British Red Crescent Society and The Indigent Muslim Burial Fund.

Just prior to Anik’s death, the Trustees again began mooting the purchase of a suitable site to establish a Muslim place of worship in East London. On the 9th of December, Sir Firoz Khan Noon, (High Commissioner to India) reported two possible sites for consideration by the Trustees. His report was as follows:

[…There are] two possible sites both of which are now in the market. One, in Adler Street, leading out of Commercial Road, is not built on, so that building would have to be undertaken immediately. Further it is quite close to a Jewish place of worship. The other nos. 446 and 448 Commercial Road, [are buildings] which with some alteration would be suitable. The corner site No. 450 is also to let, but not for sale. The price asked for 446 and 448 is about £2,000. Some of the rooms could be converted into bedrooms for

the use of sailors and other Moslems visiting London. Some could be let out as shops. No. 450 could also be used, if it were decided to take a lease of it.45

The meeting resolved to pursue the option of purchasing the Commercial Road buildings with further enquiries being made by way of a sub-committee under the guidance of the newly appointed Honorary Secretary, Sir Ernest Hotson. Sir Hotson had spent most of his career in the Indian Civil Service and had gained a reputation for having ‘cheated death’ after escaping an assassination attempt in Poona while inspecting Ferguson College as the acting Governor of Bombay. It was reported at the time that a student of the college fired two shots at him from a revolver, “the first shot struck Sir Ernest Hotson’s coat just above his heart, but was deflected by a metal stud and a pocket book. The second shot missed him”.46

The acquisition of property for use as a mosque roughly coincided with the outbreak of World War Two, the outcome of which would bring more Muslim ‘Lascars’ to the East End of London, growing the demand for a Mosque even further.47 After the passing of the Rt. Hon. Lord Lamington on the 18th September 1940,48 and under the dedicated leadership of the LMF’s new Chairman, Lt. Col. Sir Hassan Suhrawardy, an adviser to the Council of the Secretary of State for India and a trustee of the Nizamia Mosque Trust, the purchase of property numbers 446, 448, and 450 Commercial Road, London E1 was completed in late December, 1940. The total cost of the properties was £2,800 (no. 450 being purchased for £1,050, and nos. 446/448 for £1,750).49 The timing of the purchase could have been more fortunate given that WWII was well underway and a wave of German Luftwaffe bombers had begun a campaign over the skies of London. The newly attained mosque would escape the resulting attacks with minor damage. The LMF was subsequently forced to cover the costs of repairs and renovations to the buildings to make them more fit for purpose, and of course to prepare for the planned opening ceremony. At this time it was also agreed that the Jami’at-ul- Muslimin would rent No. 450 Commercial Road and be appointed to organise prayers and other religious functions based at the new East London Mosque and Islamic Cultural Centre.50

With further Executive Committee vacancies opening up and the opening ceremony of the new Mosque premises just over a week away, changes were to come to the LMF. His Excellency Hassan Nachat Pasha the Egyptian Ambassador, and H. E. Sheikh Hafiz Wahba, the Minister of Saudi Arabia were approached to become trustees of the Fund, with Hassan Nachat Pasha agreeing to serve as Vice-President. Sir Ernest Hotson and Colonel Stewart F. Newcombe were elected Joint Hon Secretaries and Sir John A. Woodhead, namesake of the Woodhead Commission that aimed at a mutually agreeable plan to divide Palestine only three years earlier assumed the role of Hon. Treasurer. Woodhead would commit the next nineteen years to the Executive Committee and would be the last of the non-Muslims to serve the LMF in an official capacity.

The British Council offered the LMF a capital grantof£100(anda possible recurring annual grant of £75) to stock a reading room at the Mosque.

With somewhat of a buzz around proceedings, the British Council offered the LMF a capital grant of £100 (and a possible recurring annual grant of £75) to stock a reading room at the Mosque and Cultural Centre with a variety of literature. The task of procuring newspapers, periodicals and books was delegated to Colonel Stewart F. Newcombe (Loyal friend to T. E. Lawrence and legendary

veteran of the Palestine Campaigns during the Great War51); while Professor Arthur J. Arberry (orientalist academic and notable translator of the Qur’an) was asked to acquire publications in Arabic, Urdu, Persian and other Oriental languages.52 Public lectures were also planned at the new premises. Another acclaimed translator of the Qur’an, political activist and Muslim scholar, Abdullah Yusuf Ali returns to London and resumes his position as a trustee. His previous tenure only lasted seven months due to his departure for India to enter the service of the Nizam of Hyderabad in 1921.

The official opening of the East London Mosque took place on Friday 1st of August, 1941. The Jumu’a (Friday) prayer was led by H. E. Sheikh Hafiz Wahba, Ambassador of Saudi Arabia. In attendance were H. E. Hassan Nachat Pasha, Vice Chairman of the LMF and Egyptian Ambassador to Britain, LMF Trustees, representatives from the Jami’at-ul-Muslimin, Lascars from the Pioneer Corps, seamen on leave from their duties, and others from East London’s Muslim Community. Echoing the public spirit of the time, in his Khutba (Friday Sermon), Sheikh Hafiz Wahba stated the following:

In this critical time, when rivers of innocent blood are flowing with total disregard for human suffering, and when all the evil elementsintheworldhaveunitedtodestroy every civilised and humanitarian activity, we gather here together to inaugurate this mosque [….] So on this happy occasion, let us pray earnestly to God to bestow upon the world once more the blessings of sanity, security and happiness (trans.).53

Also speaking at the opening of the mosque, the Egyptian Ambassador hinted at another ascending project that had recently been granted practical support from the wartime cabinet, the Nizamia Trust stating: “The opening of this Mosque, for which we are gathered today, means the realisation of our aspirations. We hope in the near future to establish an Islamic institution in the centre of London, a worthy project which will meet with the approval of all Muslims and which will be in keeping with Islamic traditions”.54

The Opening Ceremony was a great success and the following Friday (7th of August) the Rt. Hon. Leo Amery, Secretary of State for India paid an informal visit to the East London Mosque where he recited the first chapter of the Holy Quran (Surah al-Fatihah) from beginning to end flawlessly, creating great enthusiasm. Leo Amery was a strong advocate for a mosque to be built in London and welcomed the gift of £100,000 from the British government to the Muslim communities of London for the establishment of a mosque. The endowment was bestowed as a tribute to all of the Muslims who sacrificed their lives

fighting for the Empire.55

It took thirty-one years for a mosque to

eventuate in East London. From the vision of a few learned men in the early part of the 20th Century and the creation of the London Mosque Fund; through the immense difficulties of the Great Depression and World Wars One and Two, to the purchase of the three houses on Commercial Road, and the establishment of a permanent place of worship for the benefit of the growing immigrant Muslim community in East London: the East London Mosque and Islamic Cultural Centre. The people who worked for the LMF during this period were a considerably diverse group. In the words of the LMF Vice Chairman “This Mosque, where children and brothers who live here will find a place where they can pray, exchange religious and cultural ideas, as is the case so far as other religions are concerned, means the fulfilment of a desire very near to our hearts, and I note with pleasure that it has found support from every Muslim and every friend of Islam”.56 The Mosque gradually became enveloped into family life by the early post-war Muslim settlers, beginning with Muslim Lascars from the military and shipping industry, later followed by their families becoming links in the chain of migration from the Indian sub-continent to the Capital of the British Empire.

Still today, Muslims in London and particularly the East End continue to benefit tremendously from the enduringspirit with which numerous collaborators (mentioned and unmentioned) worked; a spirit that navigated the simple idea of a mosque in London through over three decades of a difficult half-century, from a vision in 1910 to a reality in 1941.

ENDNOTES

- For a much more comprehensive look at the history of the London Mosque Fund and East London Mosque, see Professor Humayun Ansari’s contribution to be published in an imminent volume of the Camden Series (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

- Tibawi, A L. (1981). “History of the London Central Mosque and the Islamic Cultural Centre 1910-1980.” Die Welt des Islams., p. 196.

3. See British Library: L/P&J/12/486, f. 40.

- The Times, October 18, 1924, p. 8, Col D.

5. The Times, April 4, 1911, p. 10, Col. D.

6. The London Mosque Fund Executive Committee Minute Book. Archives of the East London Mosque Trust, London, 1910 -1951.

7. This would amount to over £600,000 in today’s money. (http://www.thisismoney.co.uk/historic-inflation-calculator, accessed 15 April, 2011).

8. The London Mosque Fund Executive Committee Minute Book. Archives of the East London Mosque Trust, London, 1910 -1951.

9. Meeting of the Trustees; 7th April, 1911: The London Mosque Fund Executive Committee Minute Book. Archives of the East London Mosque Trust, London, 1910-1951.

10. Ali, Syed Ameer (1985). Memoirs and Other Writings of

Syed Ameer Ali. ed. Wasti, Syed Razi. (Delhi: B.R. Publishing Corporation), p.106.

11. Westminster Gazette, December 20, 1917, p. 2, Col. C.

12. Op. cit. Ali, Syed Ameer. Memoirs… p. 106.

13. See: http://thepeerage.com/p32025.htm — accessed 19 April, 2011.

14. Wasti, S. T. (1993). “Halil Halid: Anti-imperialist Muslim Intellectual.” Middle East Studies 29.3, pp. 559-579.

15. Patel, Zarina (2002). Alibhai Mulla Jeevanjee. (Nairobi: East African Educ. Publishers), p.37.

16. The Times, 20 September, 1912.

17. Op. cit. The London Mosque Fund Executive Committee Minute Book.

18. Arnold dedicates the second edition of ‘The Preaching

of Islam’ to Morison ‘in token of long friendship’. See: Arnold, T W. (1913). The Preaching of Islam. 2nd Edition. (London: Constable and Co.).

19. Morison was made principal of MAO College in 1899.

See: Aligarth Movement; http://aligarhmovement.com/ Theodore_Morrison — accessed 18 April, 2011.

20. In his will, Lord Rothschild requested that his private papers be destroyed. Thus, very little is known about his personal life.

21. Joyce, R B. “Lamington, second Baron (1860 – 1940).” 1983. Australian Dictionary of Biography. 14 April 2011 <http://www. adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A090657b.htm>.

22. The New York Times, 6 September, 1900.

23. See: http://www.thepeerage.com/p6855.htm#i68546

– accessed 19 April, 2011.

24. Meeting of the Trustees; 20th March, 1911, The London Mosque Fund Executive Committee Minute Book

25. Ansari, Humayun (2004). “The Infidel Within” — Muslims in Britain Since 1800. (London: Hurst), p.41.

26. According to Adams, the term ‘Lascar’ is probably from the Persian and Urdu word lashkar, meaning ‘an army.

Adams, Caroline (1987). Across Seven Seas and Thirteen Rivers. (London: THAP Books), p. 15.

27. See: www://www.britainsmuslimsoldiers.co.uk/images/ w1.pdf — accessed 14 April, 2011.

- Mahmood, Jahan (2011). “Remembrance Sunday: From allies to terrorists?” 26 April. “Let Us Build Pakistan” http:// criticalppp.com/archives/29303 — accessed 26 April, 2011.

29. London Mosque Fund Declaration of Trust (19 November, 1926). Archives of the East London Mosque Trust, London.

- Ibid.

31. The Times, 26 April, 1926.

32. For Syed Ameer Ali’s obituary see The Times, August 4, 1928, p. 14, Col. B.

33. See letter from Syed Hashimi to A. Anik, 26th February, 1931: The London Mosque Fund Executive Committee Minute Book.

34. Time Magazine, 22 February, 1937. http://www.time.com/ time/magazine/article/0,9171,770599,00.html — accessed 21 April, 2011.

35. See: Letter from M. M. Picthall to A. N. S. Anik, 3rd March 1932. The London Mosque Fund Executive Committee Minute Book.

36. Clark, Peter (1986). Marmaduke Pickthall-British Muslim. (London: Quartet Books), p.63.

38. Op. cit. Tibawi, A L. “History of the London Central Mosque… “ p. 196.

37. Letter from M. M. Picthall to A. N. S. Anik, 3rd March 1932. The London Mosque Fund Executive Committee Minute Book. 39. The London Gazette, Issue 33664, (25 November 1930), p. 11; Issue 34325, (22 September 1936), p. 4; and Issue 34370, (12 February 1937), p. 8. http://www.london-gazette.co.uk

– accessed 21 April, 2011.

40. Jamiat-ul-Muslimin Annual Report: (1934-35), Archives of the East London Mosque Trust, London.

41. Meeting of the Trustees; 13th May, 1936: The London Mosque Fund Executive Committee Minute Book.

42. News Footage of Governor Sykes delivering a public message can be viewed here: http://video.google.co.uk/vide oplay?docid=5127656633369223434&q=%22Sir+Frederick+S ykes%22# — accessed 21 April, 2011.

43. http://www.rafweb.org/Biographies/Sykes.htm — accessed 21 April, 2011.

44. Meeting of the Trustees; 9th December, 1938: The London Mosque Fund Executive Committee Minute Book. Archives of the East London Mosque Trust, London, 1910-1951

45. The Argus (Melbourne, Australia): 23 July, 1931. P. 8, Col. D.

46. Op. cit. Ansari, Humayun. “The Infidel Within” p. 51.

47. The Rt. Hon. Lord Lamington had been a committed supporter of the London Mosque Fund for nearly 25 years. 48. Meeting of the Trustees; 6th January, 1941: The London Mosque Fund Executive Committee Minute Book.

49. Ibid, Meeting of the Trustees; 23rd July, 1941.

50. Webber, Kerry. In the Shadow of the Crescent. (unpublished). See: http://shadowofthecrescent.blogspot. com/ — accessed 21 April, 2011.

51. Meeting of the Trustees; 14th August, 1941: The London Mosque Fund Executive Committee Minute Book.

52. Opening Ceremony Booklet of the East London Mosque and Islamic Cultural Centre, (August 1941), p17.

53. Ibid, p.12.

54. Op. cit. Tibawi, A L. “History of the London Central Mosque…” pp. 200-201.

55. Op cit. Opening Ceremony Booklet… p12.

*HAMZAH FOREMAN

Recent Comments